"Anytime Movies" II: Citizen Kane

So obvious a choice.

So obvious a choice. Yet “Citizen Kane” (or RKO 281) has been fielding off re-appraisals and critical backlash since the day of its premiere. Is it really "the greatest American film ever made?"

Yes.

So far….

Part of the argument against it is that it can’t be since it was the product of a 26 year old who had never made a film before. But Orson Welles was a 26 year old who grew up pampered and precocious—who read Shakespeare at an age when other kids are reading Seuss. As a teen he made his way in the world by his brio and his considerable talents and his nerve to try just about anything. He was an artistic sociopath who staged alternative Shakespeare productions and avant-garde radio plays for years before be given, as Kane puts it, “the candy store”—a carte blanche contract with a film studio to make any film of his choice, any way he wanted with final cut and a stipulation that said no one could alter it in any way in perpetuity (This is the reason why Turner Broadcasting in its rush to colorize movies could never put so much as a pink pixel to “Citizen Kane.” Some contract!). With it, he gathered his seasoned Mercury Theater actors (some of whom would go onto major Hollywood careers), one of the most innovative and painterly cinematographers, Gregg Toland, young, daring editor Robert Wise, the arrogant and brilliant composer Bernard Herrmann, and the amazing technical crew at RKO who produced such amazing feats as “King Kong” and the Astaire-Rogers musicals and turned them loose on Herman Mankiewicz’s long-in-the-planning screenplay that he believed could never be produced.

Out of all that talent at the top of its game, Welles produced the best American movie ever made, and as a reward he was never allowed that freedom again. Ever.

No good movie goes unpunished.

His next film, “The Magnificent Ambersons” was a more mature and accomplished–looking film, but RKO chopped it up. re-shot the ending into a certain incomprehensibility and threw it on the bottom of a cheesey double bill. Welles’ Falstaff movie “The Chimes at Midnight” was the project closest to his heart, and might be better if not for the logistical and technical hurdles Welles had to jump in order to make it.

But “Kane” is the grail—the stuff of legend, and has been looked on ever since with avarice by would-be auteurs with more guts than talent, and therein lies the danger. That reputation could make "Kane" as cold and lifeless as one of the statues in Xanadu’s basement. It’s actually more like one of Susan Alexander Kane’s puzzles—intricate and maybe unsolvable without a lot of effort. There’s one shot where Welles shows his hand. It occurs after Susan has left him, accompanied by the screeching cockatiel superimposed on the screen (“I wanted to wake the audience up at that point,” Welles joked. Really, Orson? Right there?) and right after he trashes her room—destroying the acquisitions of her life—and Kane picks up the snow-globe that will fall from his hand at his death. “Rosebud,” he murmurs (both times) and then walks as in a daze out of her room, into the hall, and past the servants. He then crosses through a mirrored hallway that reflects an endless line of Kanes that recede and disappear. After Kane (and his many reflections) has passed, the camera then pushes into the mirror and out of the reverie of the butler (“Sentimental fella, aren’t you?” “Mmm. Yes and no.”)

That shot is the exit from the worlds of memory through which we have seen many reflections of Kane—the house of mirrors that makes up the bulk of “Citizen Kane,” the movie. It is also our last image of Kane, himself, in the film. He’s talked about through to the end, of course, but that splintered mirror-shot is our final impression of him (Kane—and Welles—are not even seen in the End Credits review of actors). At that point it becomes clear (as crystal) that the entire film is like that hall of mirrors that reflected back the aspects of Kane important to each narrator—a process that began with the newsreel that quickly jumped through the highlights of Kane’s life as a public figure and set up the film’s surface mystery—what is the meaning of Kane’s last word (and so serves as a stand-in for “who was Kane, really?”).

In the course of the various reflections there are all sorts of legerdemain—little tricks and in-jokes—that Welles, who was an amateur magician, clearly loved pulling off even if an audience didn’t immediately “get” them. One of my favorites is the craning shot through the model of the “El Rancho” nightclub where Susan Alexander performs and drinks herself into a stupor every night. The night of Thompson’s first visit it’s storming outside and flashes of lightning hide the camera’s passage through the roof sign and through the glass transom into the nightclub inside. When, half the movie later, we again travel through that transom it’s broken—presumably by our first trip through it. In the film’s original framing (unfortunately not in the DVD presentation) there is the slightest nudge of the camera to the right in the rather severe shot of Mrs. Kane signing little Charles away to the banker, and we see, just on the edge of the frame, that significant snow-globe that keeps popping up in dramatic moments. In the newsreel there is a shot of a newspaper of the entire Kane family. Later in the film, we actually see that shot being taken. Another is the way Kane’s hectoring “Sing-Siiiiing!” to “Boss” Jim Gettys is cut off by a shutting door, but continues by a braying car-horn out on the street. These are little filigrees to the grand architecture of lighting, framing and editing tricks that Welles and his crew pull off.*

But that central question “who was Kane?” is purposely never answered, not by a word, not by an object, and not by a person. In the end, the film says that it can’t solve the problem, that it can only present it, and leave us with the acknowledgement of its complexity.

So what are we left with as the remnants of Kane and his life fly up from the furnace of Xanadu? An answer to the mystery of "Rosebud," but not an answer to the man. For Kane was many things, but as Kane himself passed judgment on himself, he was never great. Given gifts that many of us will never ever have, he ultimately squandered them. Insular, wasteful, in his house of mirrors, he is left alone to contemplate himself.

We all have our gifts. What do we do with them? “Citizen Kane” is like that glass globe that we can peer inside and see the illusion of life…and consider our own lives. And in the end we are left with its final image to contemplate, and one may consider that Kane was a master illusionist himself, pretending greatness where there was none, and utilizing the very same tools used by those other illusionists—magicians and very young film directors--to create those illusions.

Those tools being smoke…and mirrors.

Anytime Movies are movies I can watch anytime, anywhere. If I see a second of it, I can identify it. If it shows up on television, my attention is focused on it until the conclusion. Sometimes it’s the direction, sometimes it’s the writing, some times it’s the acting, sometimes it’s just the idea behind it, but these are the movies I can watch again and again and never tire of them. There are ten. This is Number 2.

2. Citizen Kane

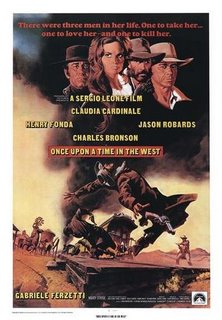

3. Once Upon a Time in the West

4. -Only Angels Have Wings

5. The Searchers

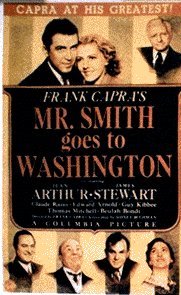

6. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

7. Chinatown

8. American Graffiti

10. Goldfinger